The following is a transcript of a talk I gave as part of our performance Data Mutations - Game of the Year Edition in 2018. You can watch a (not amazing quality) video of the performance here.

For most game artists, stories about bad labour practices in the video game industry are old news.

In the last couple of years, there were numerous reports about exploitative working conditions, sobering tales of gross underpayment, severe overworking often known as "crunch", lack of overtime compensation, no job stability and the alarming absence of unions.

This toxic relationship with labour is not limited to the industry's biggest players and similar problems exist in the indie scene, where artist will often endanger their physical and mental health, sometimes being tougher on themselves than any boss would be, only to stay competitive, to ship their product on time and to get a shot at their dreams.

This has been going on for years and might provide a glimpse at how many of us may be working in the years to come... and how many of us are already working now.

The fact that the video games industry seem so representative of current labour practices and even seem to anticipate future labour practices, is not mere coincidence.

Seeing that games and work have always been strangely related, it makes complete sense that the video game industry has become a sort laboratory for the incubation of new strategies of capitalist exploitation.

There is an essential proximity between work and play. Both are two different sides of the same coin, like inverted mirrors of themselves.

In video games the permeability of work and play becomes particularly apparent.

One essential aspect of work has always been what I will call terraforming - the act of domesticating nature and restructuring it to adapt it to our needs.

This allows accumulation - of food, of raw materials like coal or wood, of wealth in all its forms.

Both of these essential functions of labour are dramatically over-represented in video games.

The terraforming is obvious - think of Sim City, Civilisation, Rust, Minecraft, etc. But the accumulation part is even more present - from collecting coins in Mario, to competing for points in almost every game around.

The proximity of games and labour is even more apparent if we consider their shared aesthetics.

After all, we play video game on a computer, which is not only the main tool of modern capitalist labour but also the pinnacle of a long list of technologies designed for one of the most ancient of jobs: the accountant.

In a digital age when more and more jobs are done on computer screens glimmering with obscure interfaces like Google Adwords or impenetrable Excel sheets, it appears that video games and modern work share a kink for the same visuals: complex windows filled with statistics, status updates, task reports, progress measurements and flowcharts.

Finally, the production of video games itself has often a strange and eerie tendency of mirroring a kind of timeless labour - a bastard child between the hard physical labour of our past industrial society and the contemporary Excel grinding.

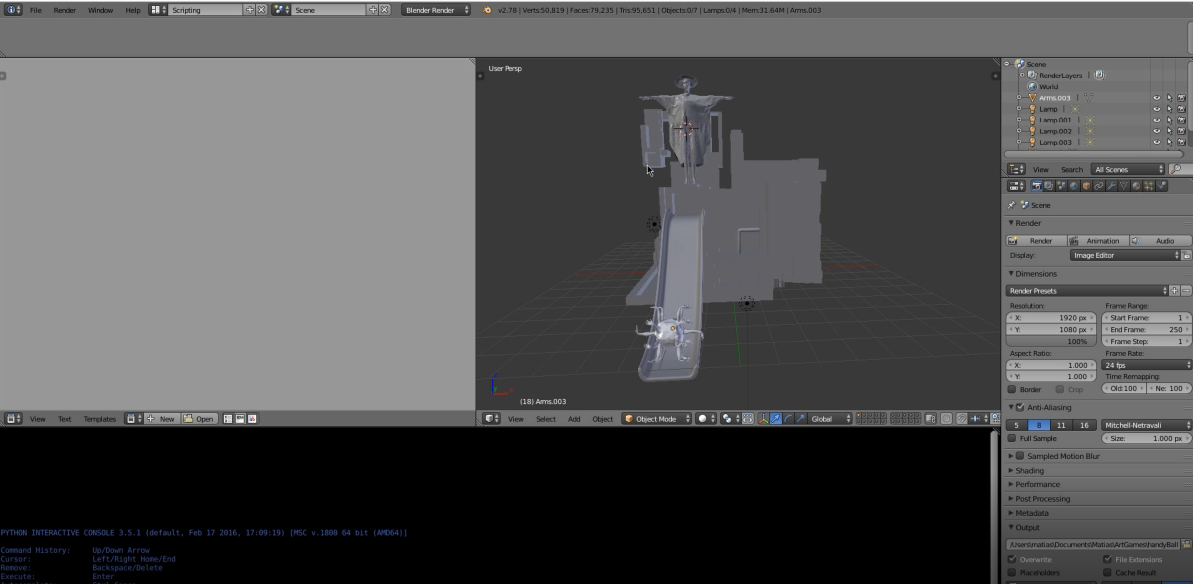

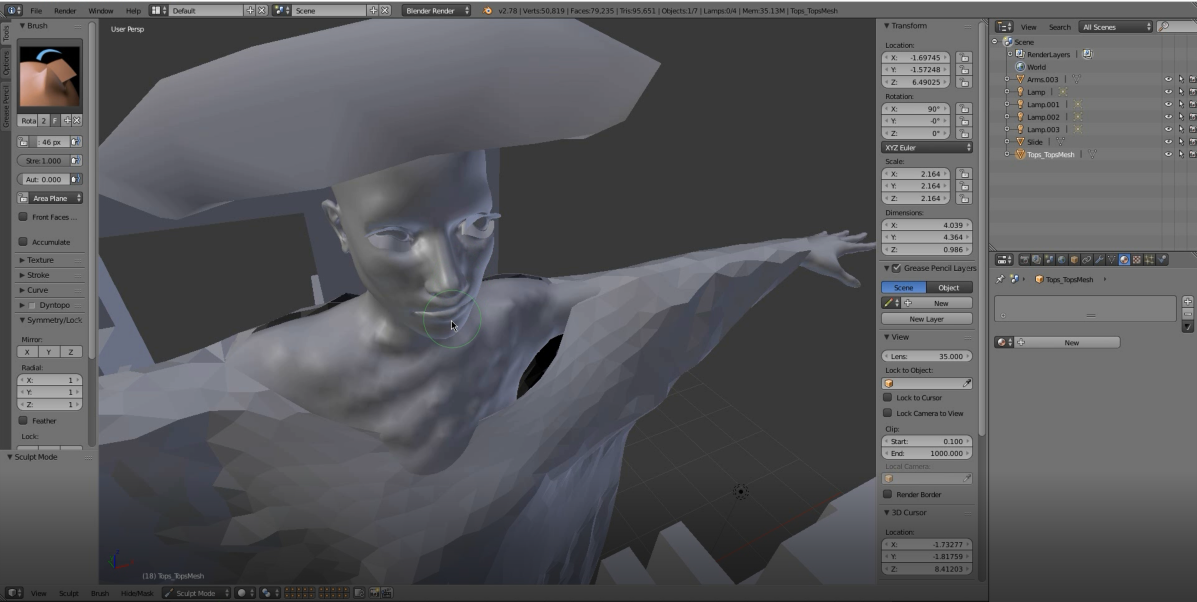

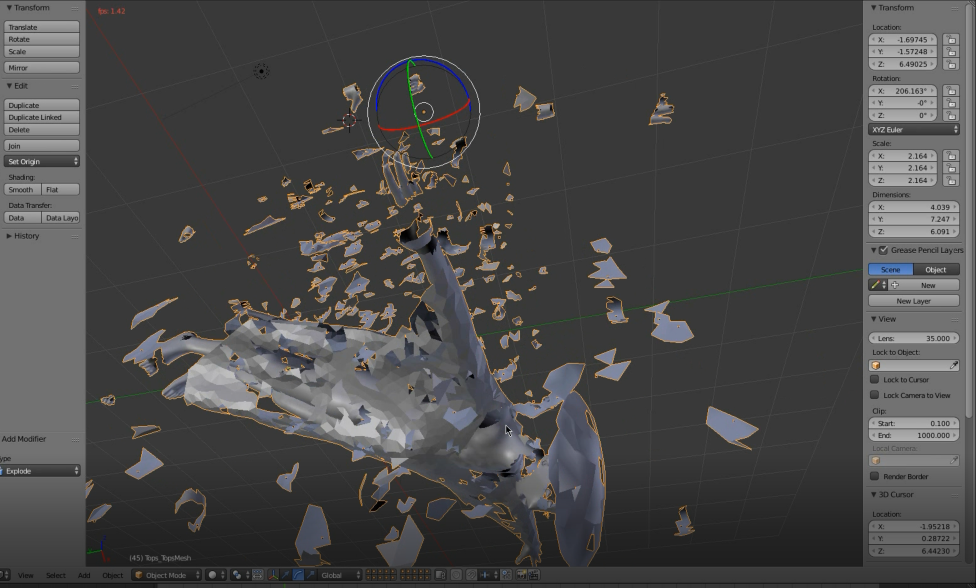

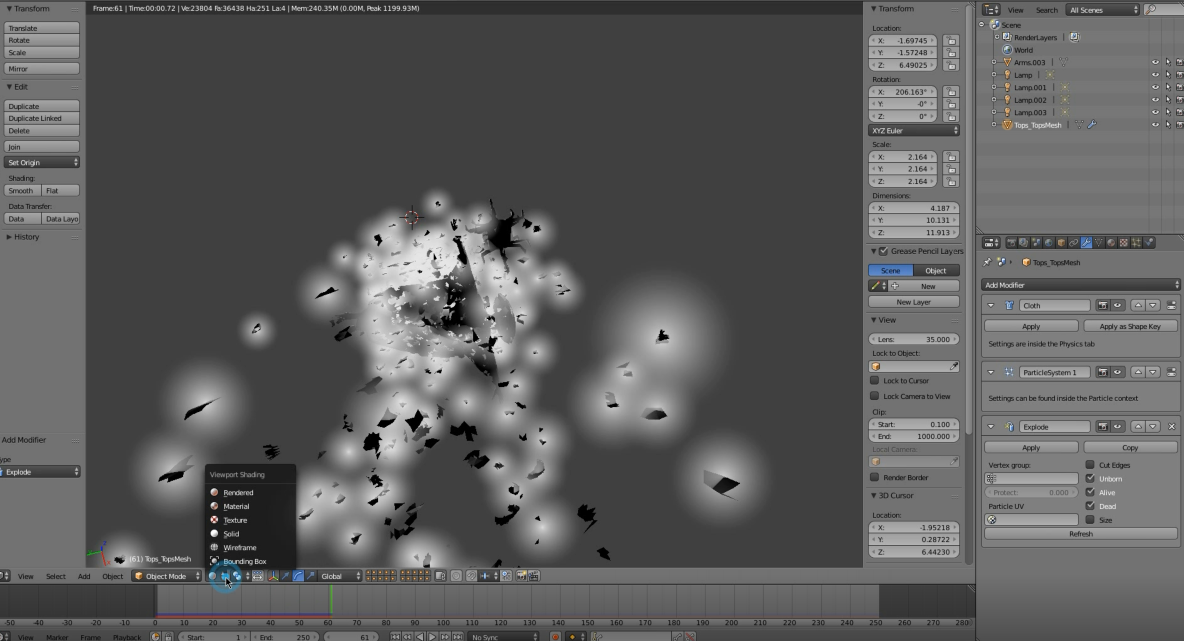

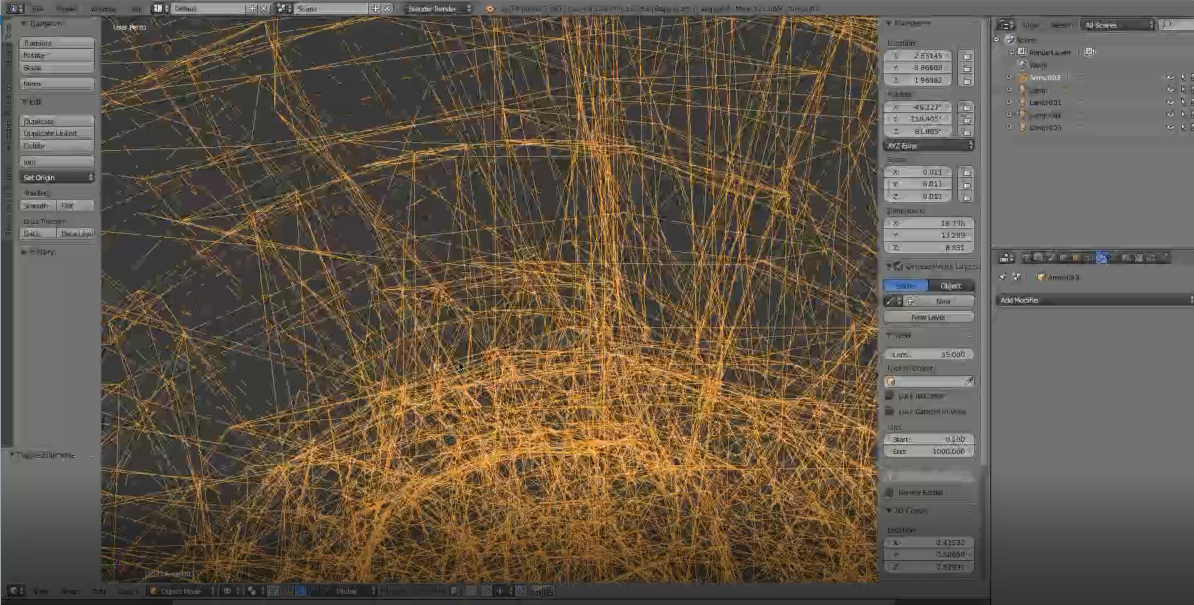

There is no better example to illustrate this than the 3D artist. In IRL they work in front of a screen, spending long hours only slightly moving the tip of their fingers in a perfect illustration of modern office work. But take a look in the virtual space behind their screen, and you will see that they are in fact sculpting, modelling clay, cutting blocks as would any sculptor, miner or blacksmith of the past.

It could be argued that the prevalence of a certain labour aesthetic in games is perfectly normal - as work has always been a central aspect of human life. In this sense, video games are merely imitating the materiality of labour, taking inspiration from an everyday concern.

However, in recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that inspiration goes in both ways.

"Gamification" has become a buzzword - the new favorite trend of the neoliberal entrepreneur.

The idea behind gamification is that games have a long tradition and experience in the art of "hooking" people, and thus, their tactics can be used to create true workaholics.

Gamification has entered the office in the form of organizing principles which try to boost productivity by speaking to the creative, play loving part of our brains: from Teambuilding and the dreaded Escape Rooms, to the RPG-like Skill Planning, slides and endless feedback loops, badges, points and a swarm of meaningless awards rewarding meaningless tasks.

The worker in this brave new world works almost as hard and sometimes more as their ancestors, but - so the story goes - they do it while having fun, because their job is not only something which has to be done: it's their passion.

Passion here is the important word. The video game industry justifies its practices by arguing that the workers are not really working... they are doing what they love. And if you are doing what you love, you are able to spend that one extra night away from your family.

This doesn't just happen in the video game industry. In the age of enthusiastic entrepreneurship, we are being trained to see work as the greatest measure of our own worth, a reflection of our dreams and the direct path to self-realisation.

This is evident in the rhetoric of every job application or job interview, from somewhat creative marketing positions to Amazon robot workers: getting results is not enough anymore, you should be passionate about your work.

I would argue that the powers of late Capitalism are rapidly making a move from the management of bodies to the management of passions.

The dream of humans as rational agents making their choices based on carefully analysed information has long been debunked. It sometimes seems that all we are is a boiling bundle of unchecked emotions, into which the powers that control us - from our bosses, to our politicians - can tap, manipulating the passions than run through us like strings at the hands of a puppeteer.

Put us in a gray office building and tell us that if we don't do the work we will not get paid: for sure we will do the work, but we will put all our efforts to do the bare minimum. Tell us that we are young creatives making the world a better place and we will burst in the office every morning, a Latte Macchiato in one hand and a wide smile on our faces, ready to pump those numbers.

The good old metaphor of the carrot and the stick was wrong all along. Leave the stick out and give us the carrot. We will soon want another carrot, and then another and another and we will continue to run after those delicious carrots until we drop dead.

But don't panic, everything is not as bleak as it sounds.

Until now, I argued that games are more or less a tool used to condition us to capitalist exploitation. But well made and well used, they might also just do the opposite and actively help us to resist… by allowing us to navigate statistical labyrinths more expertly, to train our bullshit detector and to see through the lies of the Silicon Valley mythology.

In the future, games could easily help us understand the mechanism of alienation underlying particular work situations.

Through new forms of collaborations in game development, sharing of assets and skills, and a refusal to accept the management of passions imposed on us by late capitalism, it is possible to induce spaces of creation that are not exploitative, or oppressing, but liberating.

My point is : if games are so intricately related to capitalist work and its abuse, that means that they also are uniquely qualified to reflect on it and counter attack.